I'm now [in July 2018] in a group full of compiler engineers at Facebook and learning a lot. Yesterday, I read a post by David Detlefs (summarizing a collaborative idea involving several members of his team) about how to efficiently encode strings for concatenation and since it's very clever I figured I would share it.

Problem

A lot of programs are taking a string as input and building a string as output. You can imagine the following code. Note: I'm going to use JavaScript as an example but it applies to almost all the languages out there.

var str = '\n';

for (var elem of elems) {

str += ' * ';

if (elem.isExpired) {

str += '[expired] ';

}

str += elem.name + '\n';

} |

var str = '\n';

for (var elem of elems) {

str += ' * ';

if (elem.isExpired) {

str += '[expired] ';

}

str += elem.name + '\n';

}

An example output might be

'

* Nutella

* Eggs

* [expired] Milk

' |

'

* Nutella

* Eggs

* [expired] Milk

'

What is being executed is

'\n' + ' * ' + 'Nutella' + '\n' + ' * ' + 'Eggs' + '\n' + ' * ' + '[expired] ' + 'Milk' + '\n' |

'\n' + ' * ' + 'Nutella' + '\n' + ' * ' + 'Eggs' + '\n' + ' * ' + '[expired] ' + 'Milk' + '\n'

If you implement this naively, the execution would look something like:

'\n' + ' * ' = '\n * '

'\n * ' + 'Nutella' = '\n * Nutella'

'\n * Nutella' + '\n' = '\n * Nutella\n'

'\n * Nutella\n' + ' * ' = '\n * Nutella\n * '

'\n * Nutella\n * ' + 'Eggs' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs'

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs' + '\n' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n'

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n' + ' * ' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * '

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * ' + '[expired] ' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] '

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] ' + 'Milk' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] Milk'

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] Milk' + '\n' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] Milk\n' |

'\n' + ' * ' = '\n * '

'\n * ' + 'Nutella' = '\n * Nutella'

'\n * Nutella' + '\n' = '\n * Nutella\n'

'\n * Nutella\n' + ' * ' = '\n * Nutella\n * '

'\n * Nutella\n * ' + 'Eggs' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs'

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs' + '\n' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n'

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n' + ' * ' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * '

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * ' + '[expired] ' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] '

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] ' + 'Milk' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] Milk'

'\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] Milk' + '\n' = '\n * Nutella\n * Eggs\n * [expired] Milk\n'

Because strings are immutable, we need to do a full copy of the string for every small concatenation. In practice this turn a O(n) algorithm into O(n²).

Solution 1: Change the code

If this becomes a bottleneck, instead of using a string all the way through, you can use an array and push all the string pieces to it. Once you are done building the result, you can join all the pieces together into the final string. Since at this point you know all the strings the operation can sum all the sizes and allocate exactly the right size.

var buffer = ['\n'];

for (var elem of elems) {

buffer.push(' * ');

if (elem.isExpired) {

buffer.push('[expired] ');

}

buffer.push(elem.name, '\n');

}

str = buffer.join('') |

var buffer = ['\n'];

for (var elem of elems) {

buffer.push(' * ');

if (elem.isExpired) {

buffer.push('[expired] ');

}

buffer.push(elem.name, '\n');

}

str = buffer.join('')

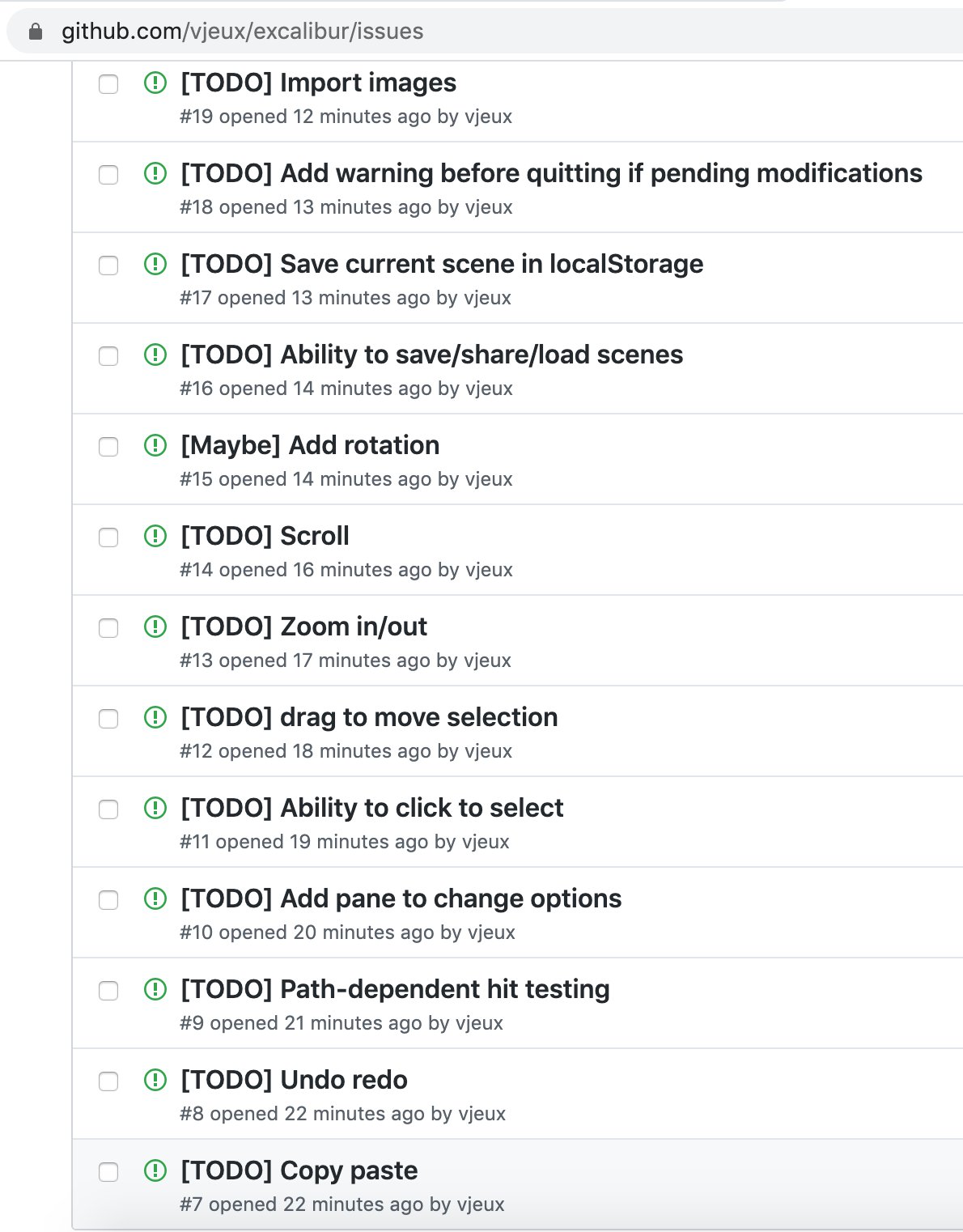

This pattern works to solve the problem but requires the programmer to know about it and the performance to be bad enough that it is worth writing code in a different way. In practice, a lot of code is not written that way and it's unclear that any amount of education will change this fact.

Note that a compiler to a bytecode format could, in many cases, make the transformation of the original code to the explicit StringBuffer code. But not in all cases, since compilers have to be conservative: if the string being concatentated is passed as an argument, all bets are off.

Broken Solution 2: Mutate the original string

The solution that comes to mind is: can normal strings act as a buffer?

The idea is that you allocate a buffer of characters and whenever you do a concatenation, you keep writing at the end of the buffer. If it isn't big enough, you allocate a bigger one, do a single copy and keep going.

var str = '\n'; // size = 1, ['\n', _, _, _, _, _, _, _]

str += ' * '; // size = 4, ['\n', ' ', '*', ' ', _, _, _, _]

// The next one doesn't fit so we need to alloc a new buffer and do a full copy

str += 'Nutella'; // size = 11, ['\n', ' ', '*', ' ', 'N', 'u', 't', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'a', _, _, _, _, _]

str += '\n'; // size = 12, ['\n', ' ', '*', ' ', 'N', 'u', 't', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'a', '\n', _, _, _, _] |

var str = '\n'; // size = 1, ['\n', _, _, _, _, _, _, _]

str += ' * '; // size = 4, ['\n', ' ', '*', ' ', _, _, _, _]

// The next one doesn't fit so we need to alloc a new buffer and do a full copy

str += 'Nutella'; // size = 11, ['\n', ' ', '*', ' ', 'N', 'u', 't', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'a', _, _, _, _, _]

str += '\n'; // size = 12, ['\n', ' ', '*', ' ', 'N', 'u', 't', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'a', '\n', _, _, _, _]

If you are curious, this is how the Java StringBuilder class is implemented. Performance-wise, this is what we want, but there's one problem...

Aliasing

You can assign the string to a variable and assign another variable with that variable. For example:

var str = '\n';

var str2 = str; // here we make an alias |

var str = '\n';

var str2 = str; // here we make an alias

In this case, both str and str2 are pointing to the same '\n' string. In the compiler literature this is called aliasing. The big question is what happens if you try to update one of the variable:

If you look at the JavaScript specification, strings are immutable meaning that you expect str2 to be unchanged but str to be:

str2 == '\n'

str == '\n * ' |

str2 == '\n'

str == '\n * '

Unfortunately, if you mutate the string like in the above solution, then both of them would be '\n * because they both point to the same underlying storage.

Solution 3: Linear Types

If you've not been living under a rock, you probably have heard about Rust and linear types. This is a fancy name to say that you cannot have aliasing: there's only a single variable that can point to a value at all time.

What this means in this case is that the line var str2 = str; would be illegal. If you want to do that, you need to do a full copy of the value so it's effectively a different one.

In practice, aliasing happens all the time in normal programs, for example calling a function with a string as argument is a form of aliasing. We wouldn't want to do full copies every time aliasing is happening.

Rust is getting away with it using a concept calling "borrowing" where you can create an alias if the compiler can guarantee that the previous variable cannot be accessed during the lifetime that the alias exists.

In my understanding, you need a strong type system in order to properly enforce those guarantees and in dynamic languages like JavaScript you would have to be too pessimistic and do way more copies than necessary when you are just passing the variable around, ruining the wins you get from building the string in the first place.

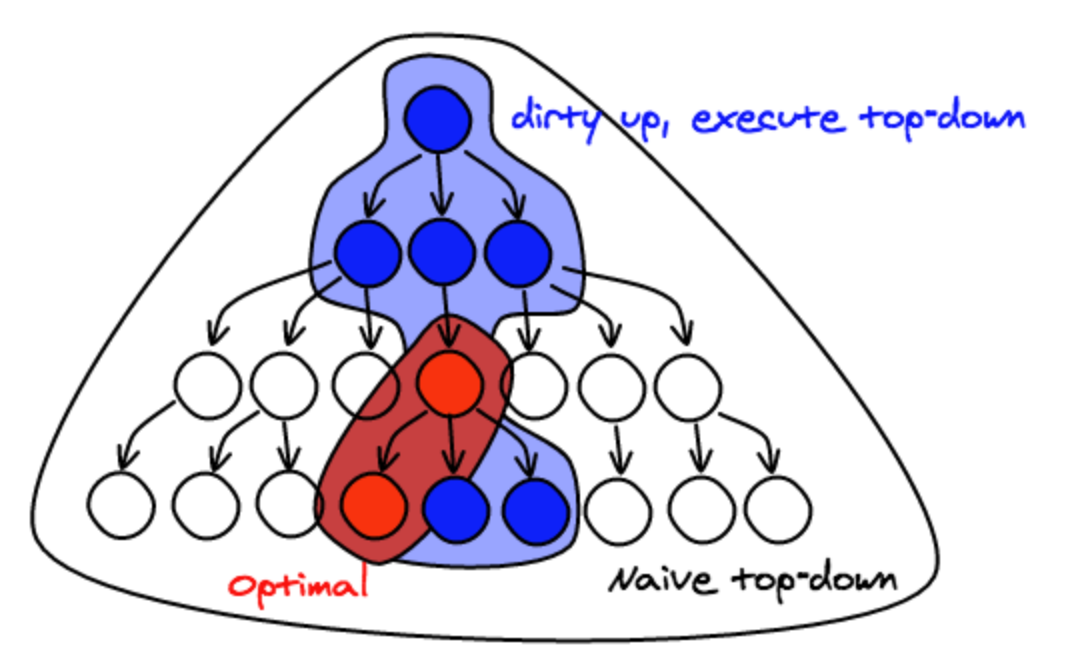

Solution 4: Size in the variable

Aliasing is usually a dealbreaker because you can mutate the underlying storage that another variable could observe. But in this particular case we can exploit the fact that the only mutation we care about is appending something at the end.

So, in the variable we not only keep a pointer to the buffer but also the size we care about. If someone else appends something at the end, it will not affect us because what's in the buffer for that size didn't change.

var str = '\n';

// buffer1, size = 1, ['\n', _, _, _, _, _, _, _]

// str : size = 1, buffer = buffer1

var str2 = str;

// str2: size = 1, buffer = buffer1

str += ' * ';

// buffer1, size = 4, ['\n', ' ', '*', ' ', _, _, _, _]

// str : size = 4, buffer = buffer1 |

var str = '\n';

// buffer1, size = 1, ['\n', _, _, _, _, _, _, _]

// str : size = 1, buffer = buffer1

var str2 = str;

// str2: size = 1, buffer = buffer1

str += ' * ';

// buffer1, size = 4, ['\n', ' ', '*', ' ', _, _, _, _]

// str : size = 4, buffer = buffer1

At this point, str2 points to buffer1 with '\n * ' but because it has size = 1 then we know it really is '\n' as intended.

The only edge case to consider is if you are trying to also concatenate str2. If the size of the variable is not equal to the size of the underlying buffer, this means that someone else clobbered the buffer. In this case, our only option is to do a full copy.

str2 += '|';

// buffer2, size = 8, ['\n', '|', _, _, _, _, _, _]

// str2: size = 2, buffer = buffer2 |

str2 += '|';

// buffer2, size = 8, ['\n', '|', _, _, _, _, _, _]

// str2: size = 2, buffer = buffer2

Conclusion

Before joining the team, I knew about the string builder pattern but I had no idea that there was so much theory behind this particular problem like aliasing, linear types... I hope that explaining those concepts in terms of JavaScript is helpful to get some insights into what's happening inside of compilers.