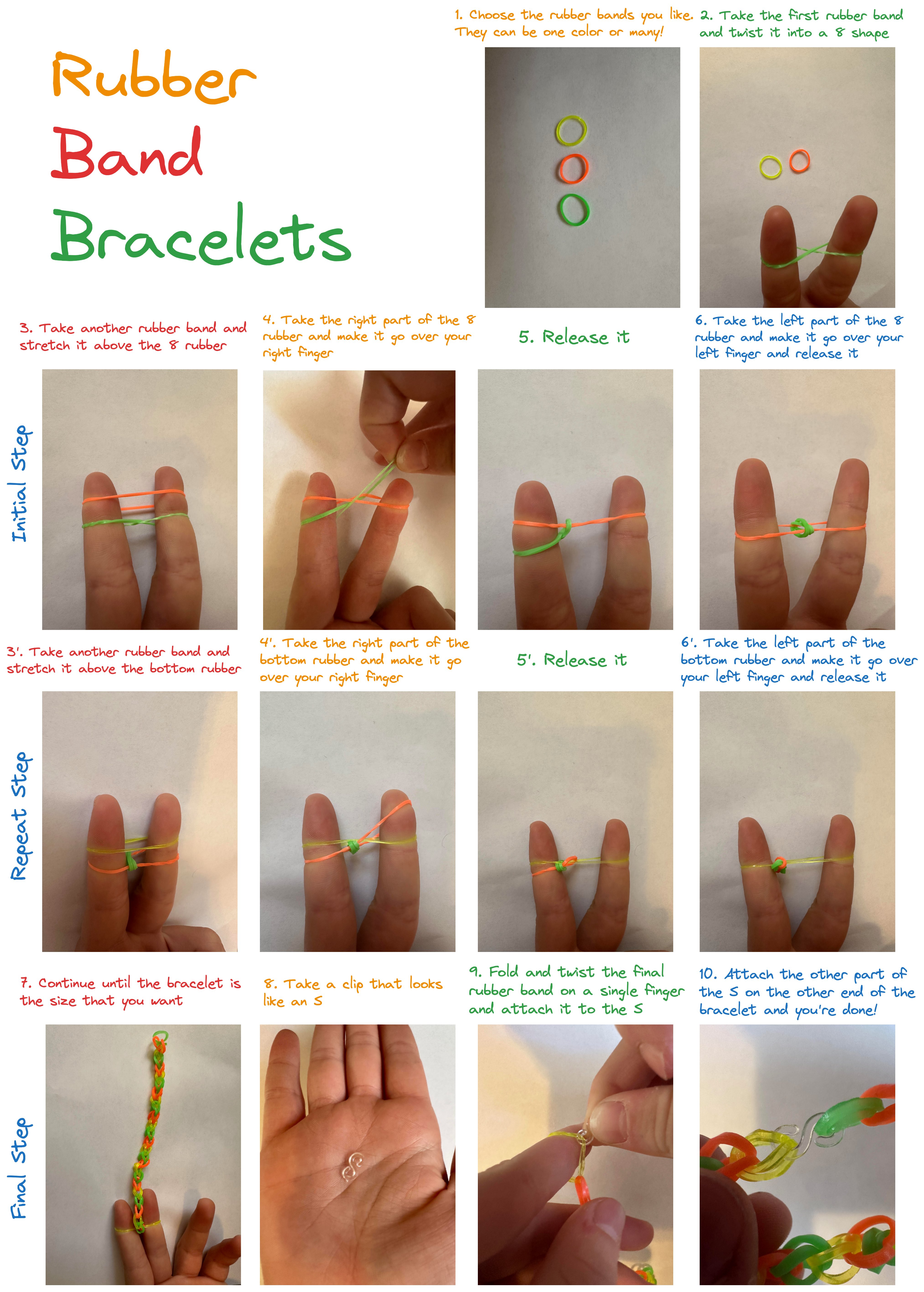

For a school activity we are organizing a rubber band bracelet making. Here is a how to we did for it. Feel free to reuse it if you're doing the same.

For a school activity we are organizing a rubber band bracelet making. Here is a how to we did for it. Feel free to reuse it if you're doing the same.

LLMs have seen a huge surge of popularity with ChatGPT by going from prompt to text for various use cases. But what's really exciting is that they are also extremely useful as ways to implement normal functions within a program. This is what I call LLM As A Function.

For example, if you want to build a website builder that will only use components that you have in your design system, you can write the following:

const prompt = 'Build a chat app UI'; const components = llm<Array<string>>( 'You only have the following components: ' + designSystem.getAllExistingComponents().join(', ') + '\n' + 'What components to do you need to do the following:\n' + prompt ); // ['List', 'Card', 'ProfilePicture', 'TextInput'] const result = llm<{javascript: string, css: string}>( 'You only have the following components: ' + components.join(',') + '\n' + 'Here are examples of how to use them:\n' + components.map(component => designSystem.getExamplesForComponent(component).join('\n') ).join('\n') + '\n' + 'Write code for making the following:\n' + prompt ); // { javascript: '...', css: '...' } |

What's pretty magical here is that the llm calls are taking as input arbitrary string but output real values and not just string. In this case it's using JavaScript and TypeScript for the type definition but can be anything you want (Python, Java, Hack...).

The function that we are using is llm<Type>(prompt: string): Type. It takes an explicit type that will be returned.

The first step is you need to have introspection / code generation from your language to be able to take the type you put and manipulate it. With this type we are going to do two things:

We will convert it to a JSON example and augment the prompt with it. For example in the second invocation the type was {javascript: string, css: string}, we are going to generate: 'You need to respond using JSON that looks like {"javascript": "...", "css": "..."}'. We are using prompt engineering to nudge the LLM to be responding in the format we want.

We also convert it to a JSON Schema that looks something like this:

{ "type": "object", "properties": { "javascript": {"type": "string"}, "css": {"type": "string"} } } |

This is fed to JSONFormer which restricts what the LLM can output to 100% follow the schema. The way LLMs generate the next token is by computing the probability of every single token and then picking the most likely. JSONFormer restricts it to only the tokens that match the schema.

In this case, the first generated tokens can only be {"javascript": " and then the LLM is left filling the blanks until the next " at which point it will be forced to insert ", "css": ", left on its own again and then forced with "}.

The great property of LLMs generating new tokens based on the previous ones is that even without the added prompt engineering, if it sees {"javascript": " it will automatically continue generating JSON and will not be likely to add all the intros like Sure, here is the response.

At this point we are guaranteed to get a valid JSON using our structure. So we can use JSON.parse() on it and then convert it to the JavaScript object we requested.

Before we implemented this magic llm<Type>() function, we'd see people adding a lot brittle logic in order to try and get the LLM to output things in the correct format, do lot of prompt engineering, add fuzzy parsing, retry logic... This was both brittle and added latency to the system.

This is not only a reliability improvement but really unlocks a whole new world of possibilities. You can now leverage LLMs within your codebase to implement functions that returns values just like any other function would, but instead of writing code to run it, you tell it what to do using text.

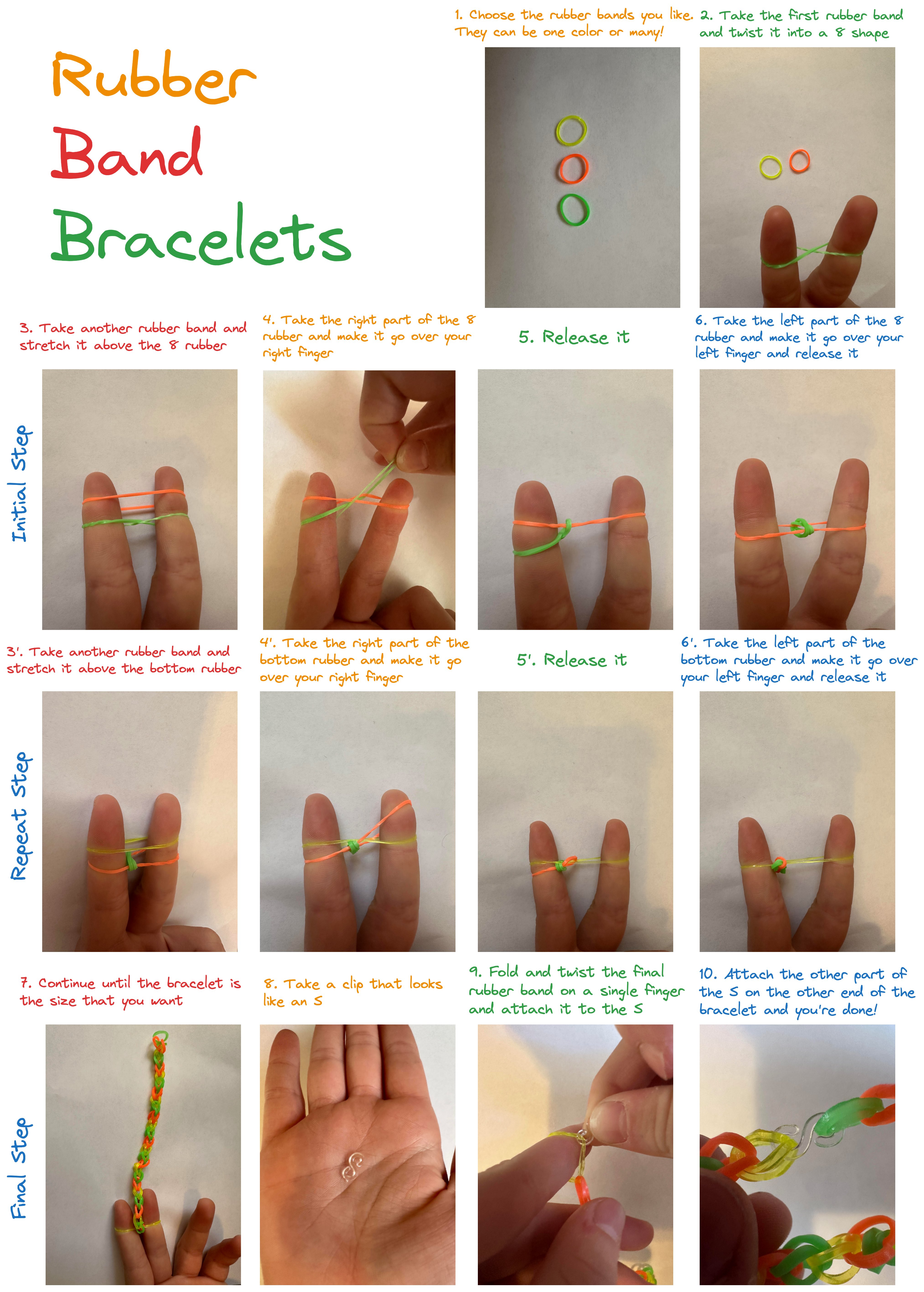

I've been playing Trackmania, a racing game, recently and they introduced a new concept called Cup of the Day. Every day a brand new map is released, for 15 minutes everyone is trying to get the fastest time and based on that time are put into groups of 64 players. Then for 23 rounds people play and the slowest ones are eliminated until there's only 1 winner left. This is super fun to play!

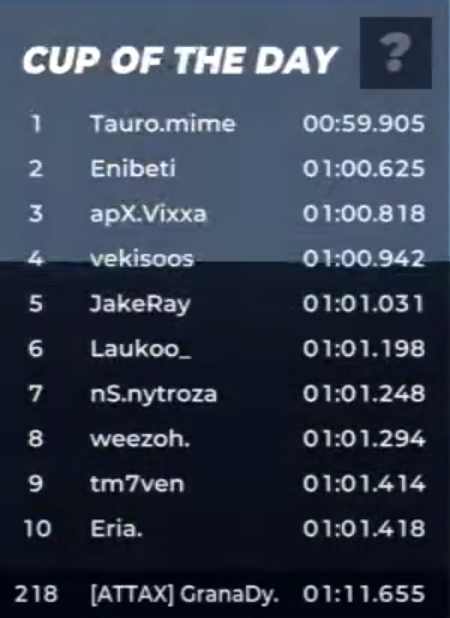

Each map has 4 times associated: "Author Time", "Gold Medal", "Silver Medal", "Bronze Medal". Not all those times are of equivalent difficulty for all the maps. I've been trying to get gold medals on all the tracks and for some it takes me a few minutes compared to hours for some others. So I've been trying to figure out a way to get a sense of how difficult it is to get.

Fortunately, there's an in-game leaderboard that tells you the times everyone made. So my plan was to scrape this leaderboard, figure out how many people got which medal and hope to get a sense of how hard the map is.

Fortunately, the website trackmania.io has all the information I needed. It has the medal times and the actual leaderboard.

Not only that but the way the website is written is a single page app using Vue that queries the data from a server endpoint using JSON. So this makes retrieving the information even more straightforward, no need to parse HTML.

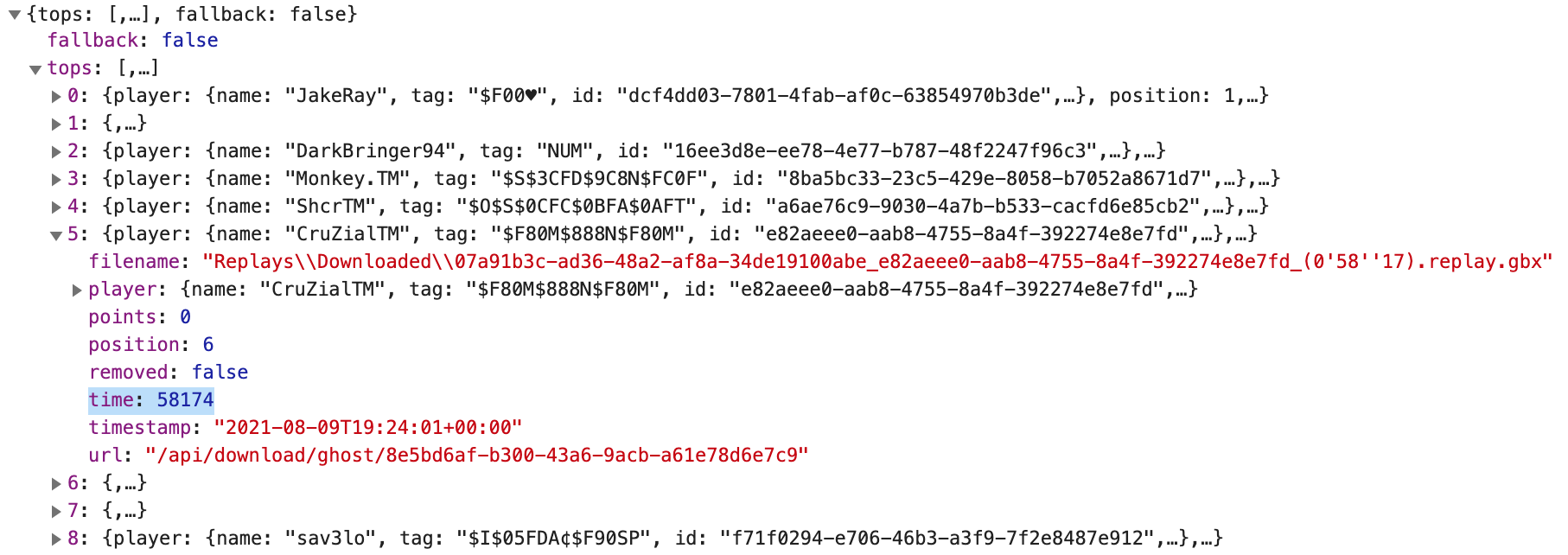

At this point, what I need is to figure out how to get the number of people that got each medal. The traditional way to do a leaderboard is to have the endpoint return a fixed number of results each time and have a pagination system. So I would do a binary search in order to find where the medal boundary lie.

But, it turns out that this was even easier, the pagination API is doing the limits based on a specific time. So the algorithm was to query the map medal times, and for each of them query the leaderboard and take the position of the first result to know how many people had the previous medal!

For example, Gold time is 1:03.000. I query the leaderboard starting at 1:03, the first person will have 1:03.012 and be at position 2310. They won't have the gold medal, only silver. But 2309 people will have either the author time or gold medal.

I decided to go with a nodejs script this time around. But you can use whatever language you want, I've been doing a lot of scraping in PHP in the past.

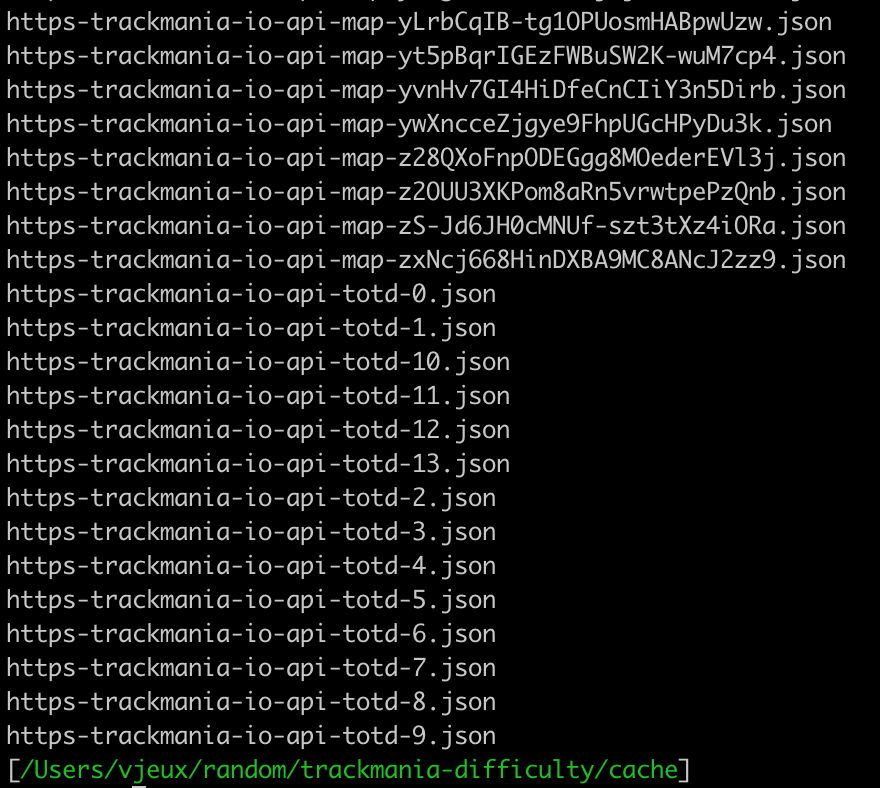

The first thing you want to do is to add a caching layer so you don't spam the server and get you banned, but also make it much quicker to iterate as the next times it'll be instant. Here's a quick & dirty way to build caching:

async function fetchCachedJSON(url) { const key = url.replace(/[^a-zA-Z0-9]/g, '-').replace(/[-]+/g, '-'); const cachePath = `cache/${key}.json`; if (fs.existsSync(cachePath)) { return JSON.parse(fs.readFileSync(cachePath)); } const json = await fetchJSON(url); fs.writeFileSync(cachePath, JSON.stringify(json)); return json; } |

And this is what my cache/ folder looks like after it's been running for a while.

The great aspect about this is that all those are single files that can be looked at manually and edited if needs be. If you someone messed up or got banned, you can delete the specific files and retry later.

If you look at the code, you'll notice that I didn't use the fetch API directly but instead used a fetchJSON function. The reason for this is that you'll most likely want to do some special things.

You probably will need some sort of custom headers for authentication or mime type. It's also a good place to add a sleep so you don't spam the server too heavily and get banned.

async function fetchJSON(url) { const response = await fetch(url, { headers: { 'Authorization': 'nadeo_v1 t=' + accessToken, 'Accept': 'application/json', 'Content-Type': 'application/json', 'User-Agent': 'vjeux-totd-medal-ranks', } }); const json = await response.json(); await sleep(5000); return json; } function sleep(ms) { return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, ms)); } |

After this, the logic was pretty straightforward, where I would just do the algorithm I described at the beginning. In order to write it, the usual way is to first implement the deepest part and test it standalone (fetching a single time) then wrap it for a map, then for a month, then for all the months.

async function fetchRankFromTime(trackID, time) { const json = await fetchCachedJSON('https://trackmania.io/api/leaderboard/map/' + trackID + '?from=' + time); return json.tops[0].position - 1; } async function fetchRanks(trackID) { const map = await fetchCachedJSON('https://trackmania.io/api/map/' + trackID); const rankAT = await fetchRankFromTime(trackID, map.authorScore); const rankGold = await fetchRankFromTime(trackID, map.goldScore); const rankSilver = await fetchRankFromTime(trackID, map.silverScore); const rankBronze = await fetchRankFromTime(trackID, map.bronzeScore); return [map.authorplayer.name, rankAT, rankGold, rankSilver, rankBronze]; } async function fetchTOTDMonth(month) { const json = await fetchCachedJSON('https://trackmania.io/api/totd/' + month); const days = []; for (jsonDay of json.days) { [authorName, rankAT, rankGold, rankSilver, rankBronze] = await fetchRanks(jsonDay.map.mapUid); days.push({day: jsonDay.monthday, month: json.month, year: json.year, authorName, rankAT, rankGold, rankSilver, rankBronze}); } return days; } async function fetchAll() { const days = []; for (month of [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]) { days.push(...await fetchTOTDMonth(month)); } console.log('data =', JSON.stringify(days.sort((a, b) => b.rankAT - a.rankAT))); } |

There are two distinct parts of the project. The first part is the data collection, described above. The second is how do you display all this data. I like to keep both separate.

In this case, the end result of the collection is a standalone JSON document where I prepend data =, that I can then include as a <script>. This way in my front-end, also written in Vue for this project, I can use that global data variable to access it.

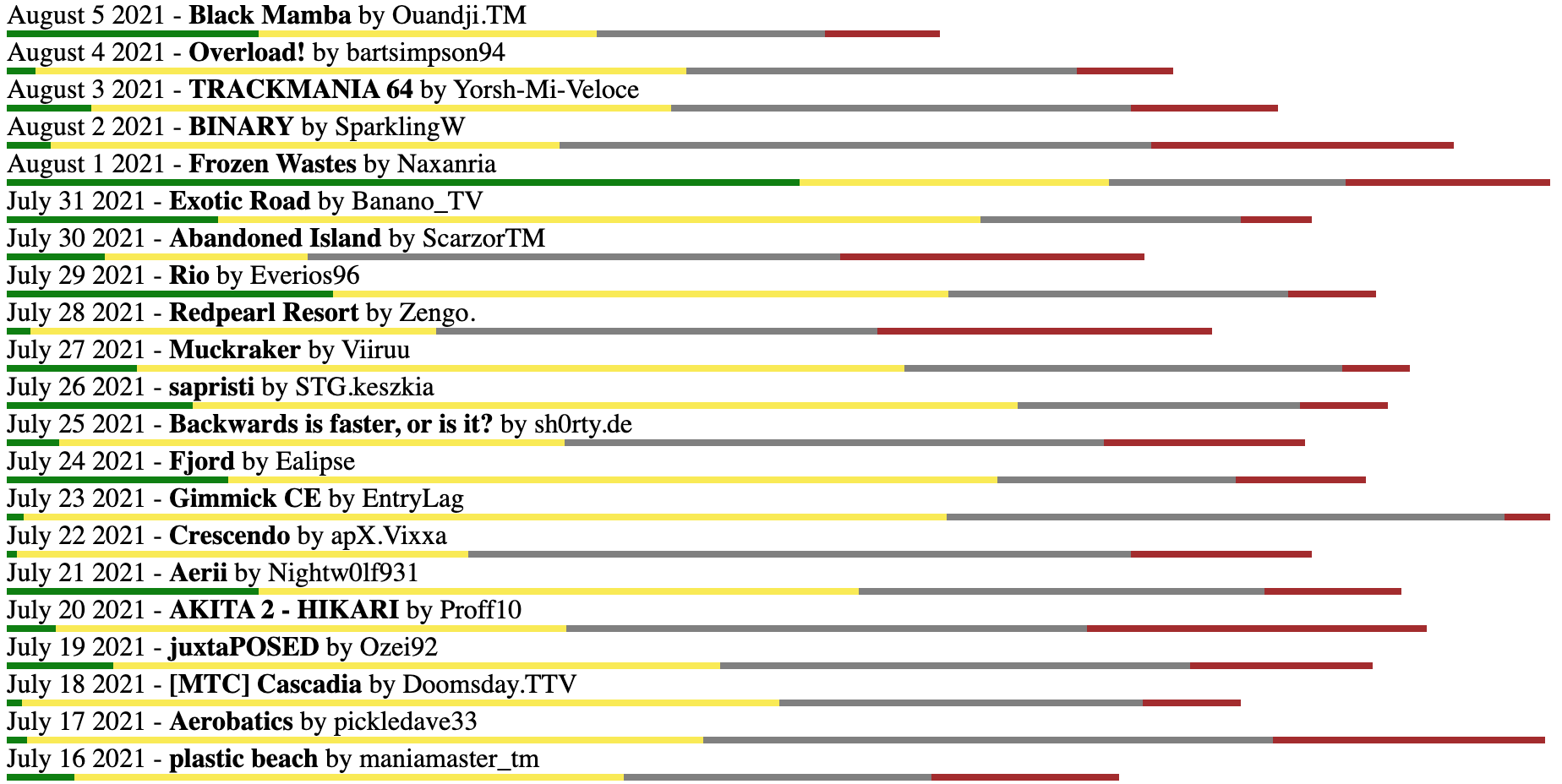

I didn't really know how to display the data. We have the number of people that have all the medals before. I started displaying an horizontal bar for each where 1px = 1 position. It worked pretty well but it was way too large.

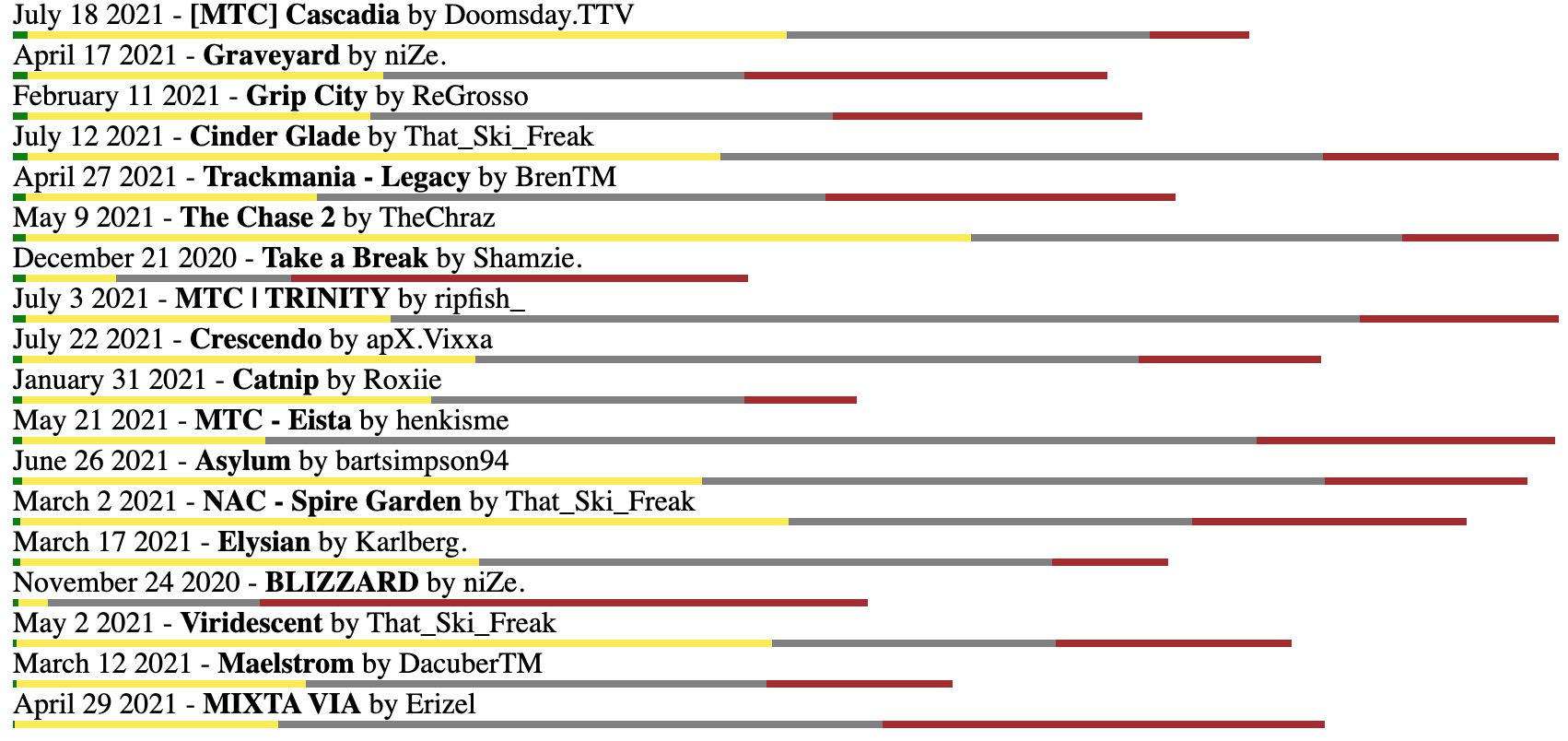

The Trackmania API stops giving any kind of precision past 10,000 so I used CSS and made all the numbers where 100% is 10,000 and it gave this results which worked well!

Since most tracks are finished by around 8k players it turns out to be working really well in practice.

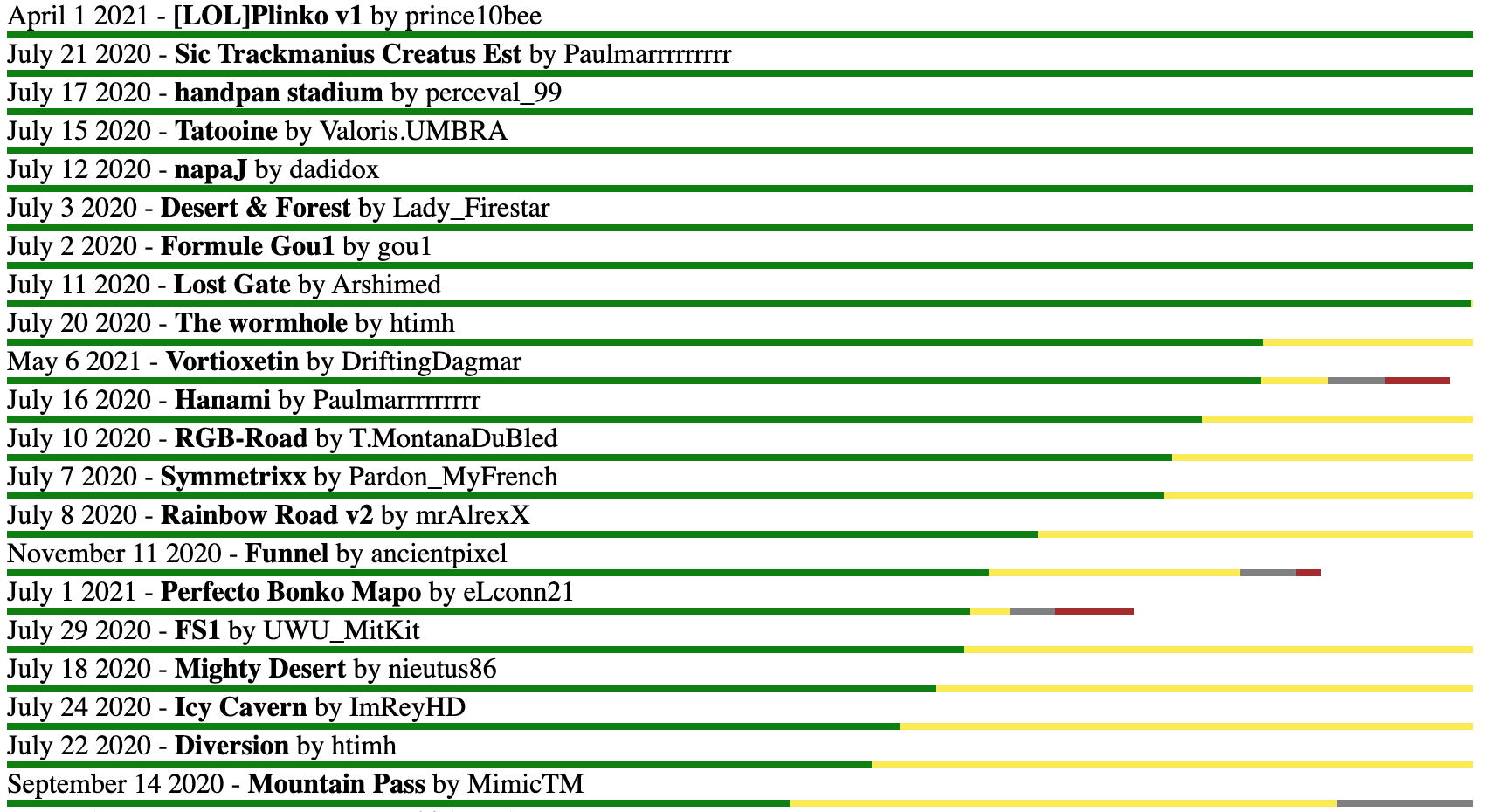

Now that we have that for every single map, we can start having fun and sort this data in many ways.

Sorting by number of people that got author time gives us what I was looking when going into this project. We can find the easiest maps:

As well as the hardest maps.

I've implemented various ways to sort such as date released, medal times and map author name. In doing so, I found out that if 10k people got a medal then the sort is going to give different orderings every time you sort them.

A quick and dirty fix is to sort the data by all the previous pivots so that it always give a stable list. It is wasteful but easy to implement by copy and pasting and the dataset is small enough that it doesn't matter much in practice.

sortAuthor: function() { this.days.sort((a, b) => (b.year * 10000 + b.month * 100 + b.day) - (a.year * 10000 + a.month * 100 + a.day)); this.days.sort((a, b) => b.rankAT - a.rankAT); this.days.sort((a, b) => b.rankGold - a.rankGold); this.days.sort((a, b) => b.rankSilver - a.rankSilver); this.days.sort((a, b) => b.rankBronze - a.rankBronze); this.days.sort((a, b) => a.authorName.localeCompare(b.authorName)); |

This was a fun project and I'm happy that I was able to figure out how hard a map was in practice. I'd like to give big props to Miss who built all the Trackmania APIs I used during this project.

Early in my time at Facebook I realized the hard way that I couldn't do everything myself and for things to be sustainable I needed to find ways to work with other people on the problems I cared about.

But how do you do that in practice? There are lots of techniques from various courses, training, tips... In this note I'm going to explain the technique I'm using the most that has been very successful for me: "casting lines".

So you want something to happen, let say implement a feature in a tool. The first step is to post a message in the feedback group of the tool explaining what the problem is and what you want to happen. It's fine if it's your own tool. The objective here is that you have something you can reference when talking to people, you can send them the link with all the context. It can also be an issue on a github project, a quip, a note... the form doesn't matter as long as you can link to it.

If the thing is already on people's roadmap or already implemented under a gk, then congratz, you win. But most likely it is not.

This is where you start "casting lines". The idea is that anytime you chat with someone, whether it is in 1-1 meetings, group conversations, hallway chat... and the topic of discussion comes close (for a very lax definition of close), you want to bring up that specific feature: "It would be so awesome if we could do X". At you see the reaction. If that person feels interested, you then start to get them excited about them building it. Find ways it connects to their strengths, roadmap, career objectives... and of course send them the link.

In practice, the success rate of this approach, in the moment, is small because people usually don't have nothing to do right now and can jump on shipping a feature that they never thought about. But if you keep casting lines consistently in all your interactions with people, at some, point someone will bite.

The more lines you cast, the more stuff are going to get done.

While this technique has been very effective at getting things done at scale, there are drawbacks to this approach. The biggest one being uncertainty around timelines. Unless someone bites, you don't know when something will be done. Some of my lines are still up from many years ago.

PS: while researching for this note, I learned that the fishing technique shown in the cover photo is called "Troll Fishing".